Material Science and Engineering

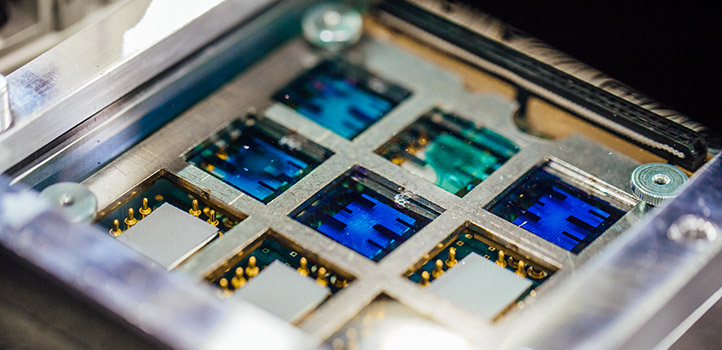

Basking in a quantum efficiency glow

Printable solar materials could soon turn many parts of a house into solar panels.

Derya Baran (left) and Nicola Gasparini are part of a team that has developed a photovoltaic organic material that captures light efficiently and that could be coated on building materials.

© 2018 KAUST

New houses could soon deliver on a long-awaited promise and incorporate windows or roof tiles that harvest solar energy, research conducted at KAUST suggests.

Derya Baran, at the KAUST Solar Center, and her colleagues have developed a photovoltaic organic material that captures light efficiently and that potentially could be coated on building materials.

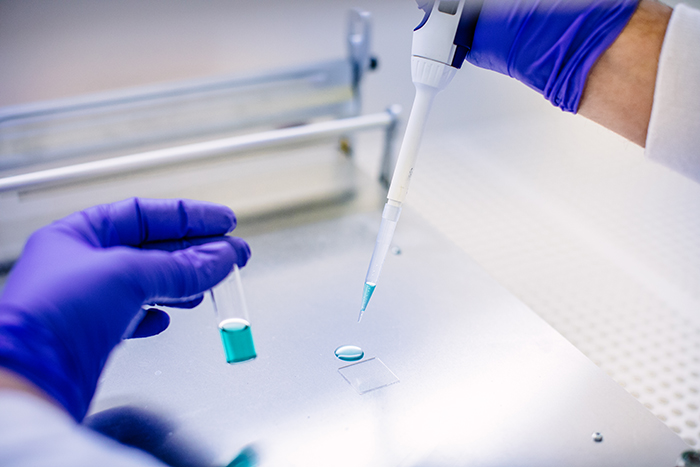

Soluble inks are used as an active layer for solar cells.

© 2018 KAUST

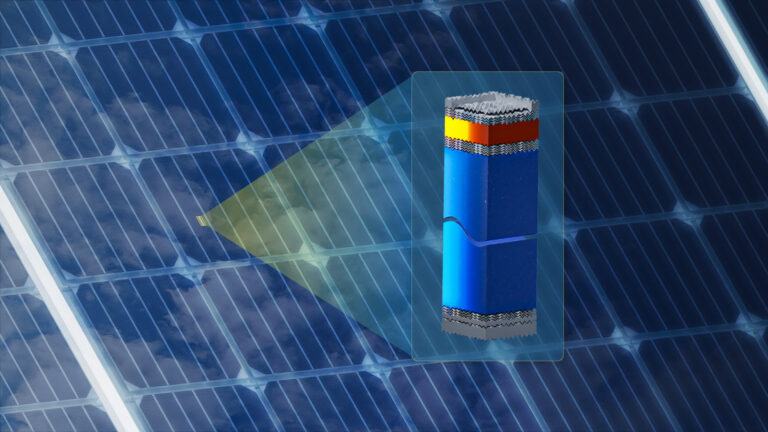

Traditional roof-mounted solar panels are made from slabs of silicon, but organic molecules can also capture energy from sunlight. These molecules could be formulated as inexpensive printable inks that are applied to regular building components such as windows. Turning sunlight into electricity is a multistep process, and the key to developing high-performance organic photovoltaic materials has been to find organic molecules that are good at every step, Baran explains.

When light strikes an organic photovoltaic material, it knocks an electron free, leaving behind a positively charged hole. If the oppositely charged electron and hole recombine, the captured energy is lost. Thus, organic solar cells incorporate a mixture of electron donor and electron acceptor molecules to draw the charges apart.

“When I started my postgraduate studies in 2015, there was a lot of hype about fullerene buckyball derivatives as acceptors, and record efficiencies were around 10-11 percent with poor stabilities,” Baran recalls. But fullerenes have several drawbacks—not least, relatively poor light absorption—so Baran has been investigating nonfullerene acceptors. “Now efficiencies up to 17 percent are being reported,” she says. “I believe these acceptors will shape the future of organic photovoltaics.”

Nicola Gasparini investigates the reliability of organic solar cells under light and thermal stress.

© 2018 KAUST

The nonfullerene acceptor, known as EHIDTBR, assessed by Baran and her colleagues offers several advantages: The team showed that as well as strongly absorbing visible light, it mixed well with the electron donor component, which is important for long-term stability and performance.

EHIDTBR was also very efficient at dissociating excitons and preventing recombination—a property that should make for easy manufacturing, Baran says. In materials where recombination is high, the light-harvesting layer must be very thin so that the charges quickly reach the electrode layer, minimizing their chance to recombine. But these ultrathin layers are challenging to manufacture. “Thicker films are easier to print, particularly when they need to be scaled up for manufacturing,” Baran says.

Scaling up the technology is the team’s next step, Baran adds. “We have a spin-out company from KAUST Solar Center and through this company we want to make photovoltaic windows for electricity generation.”

References

- Baran D., Gasparini, N., Wadsworth, A., Tan, C.H., Wehbe, N., Song, X., Hamid, Z., Zhang, W., Neophytou, M., Kirchartz, T., Brabec, C.J., Durrant, J.R. & McCulloch, I. Robust nonfullerene solar cells approaching unity external quantum efficiency enabled by suppression of geminate recombination. Nature Communications 9, 2059 (2018).| article

You might also like

Chemistry

Turning infrared solar photons into hydrogen fuel

Applied Physics

A single additive enables long-life, high-voltage sodium batteries

Bioengineering

Smart patch detects allergies before symptoms strike

Applied Physics

Two-dimensional altermagnets could power waste heat recovery

Applied Physics

Interface engineering unlocks efficient, stable solar cells

Applied Physics

The right salt supercharges battery lifespan

Applied Physics

Light-powered ‘smart vision’ memories take a leap forward

Applied Physics