Bioscience

Turning up the heat on pathogenic bacteria

Protein found in gut-dwelling pathogens changes shape under human body temperatures, leading to toxins responsible for diarrheal disease.

Stefan Arold and Umar Hameed are using structural and biophysical experiments to identify the exact part of H-NS that changes its conformation when the temperature rises, which prompts the collapse of the protein complexes.

© 2019 KAUST

Pathogenic bacteria come alive at the metabolic level when they enter the warmth of the human gut, firing up genes that encode toxins and other compounds harmful to our bodies. A KAUST-led study shows how a critical bacterial protein senses changes in temperature to slacken DNA strands and boost gene expression in diarrhea-inducing bugs.

“Having determined how these bacteria sense that they are inside humans, we could try to conceive of small molecules to perturb this mechanism,” says research scientist Umar Hameed. “Such compounds would block bacteria from adapting to their environment, which would weaken them and facilitate eliminating them.”

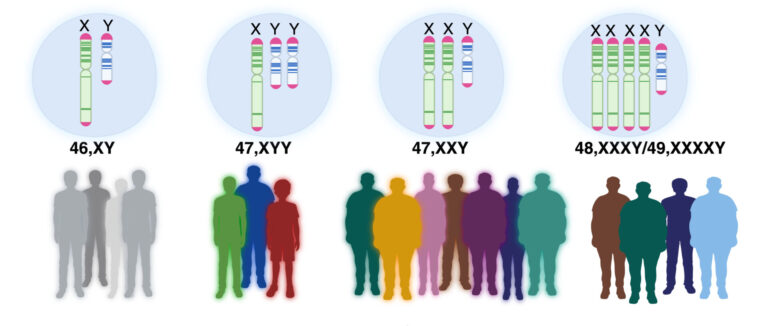

Gut-dwelling bacteria that cause food-borne illnesses, including Salmonella, disease-causing strains of E. coli and the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae, all use a protein called H-NS to condense their DNA and broadly restrict gene expression. Short for histone-like nucleoid-structuring protein, H-NS forms multiunit complexes that help the microbes stay relatively dormant when free-floating in the environment. However, these complexes must break up for the protein to release its grip on DNA, which then allows the bacteria to thrive within a warm-blooded host, explains group leader, Stefan Arold.

Before coming to KAUST, Arold, who has studied H-NS for more than 15 years, previously determined the three-dimensional shape of part of the protein. While he had shown that its complexes collapse at human body temperature, it wasn’t clear how that happened.

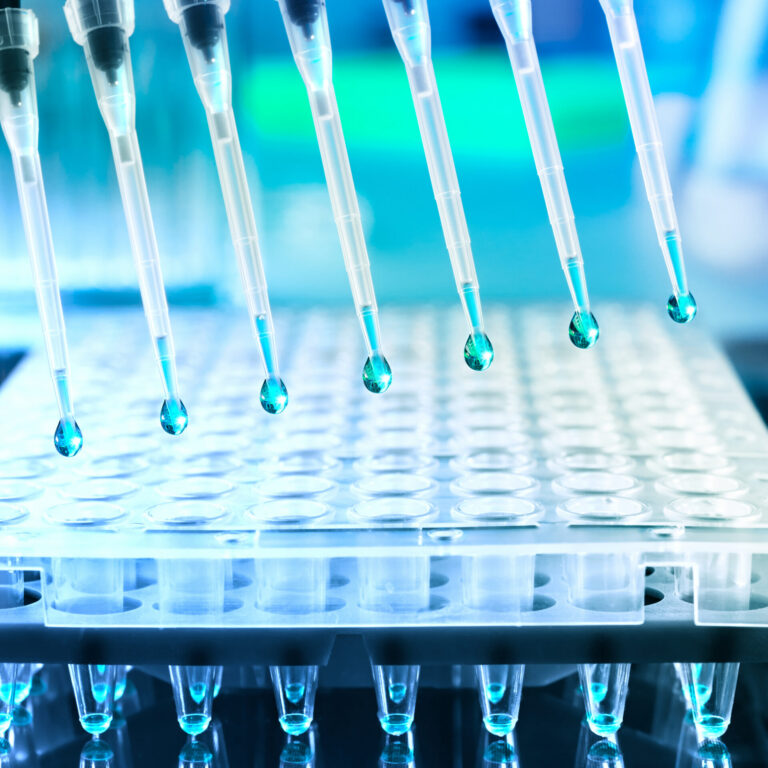

Umar Hameed performs size-exclusion chromatography, an important step in the purification of proteins. © 2019 KAUST

In his lab at KAUST with colleagues Łukasz and Mariusz Jaremko, Arold and Hameed have now combined structural and biophysical experiments. This has enabled them to identify the exact part of H-NS, dubbed site2, that changes its conformation in response to a temperature rise, prompting the protein complexes to fall apart.

Computer simulations, performed with KAUST colleague Xin Gao and Jianing Li, at the University of Vermont, USA, helped Arold’s team deepen these insights. Ultimately, they demonstrated that the partial disassembly of the H-NS complexes leads the protein to adopt a self-inhibiting form that also blocks its ability to bind and recognize DNA.

Arold and his team now hope to develop drugs that can stabilize the connection between proteins at human body temperature and prevent H-NS complexes from fragmenting. “If we can find compounds that reinforce the structure against heat-induced unfolding,” Arold says, “then bacteria would not express toxins anymore; they would remain inoffensive and be generally weakened inside humans.”

References

- Shahul Hameed, U.F., Liao, C., Radhakrishnan, A.K., Huser, F., Aljedani, S.S… Arold, S.T. H-NS uses an autoinhibitory conformational switch for environment-controlled gene silencing. Nucleic Acids Research 47, 2666-2680 (2019).| article

You might also like

Bioscience

Robust workflow built for chemical genomic screening

Bioscience

Cell atlas offers clues to how childhood leukemia takes hold

Bioscience

Hidden flexibility in plant communication revealed

Bioscience

Harnessing the unintended epigenetic side effects of genome editing

Bioscience

Mica enables simpler, sharper, and deeper single-particle tracking

Bioengineering

Cancer’s hidden sugar code opens diagnostic opportunities

Bioscience

AI speeds up human embryo model research

Bioscience