Marine Science

Checking coral reef health one tile at a time

A standardized method for monitoring the condition of coral reefs could strengthen global efforts to manage vulnerable marine habitats.

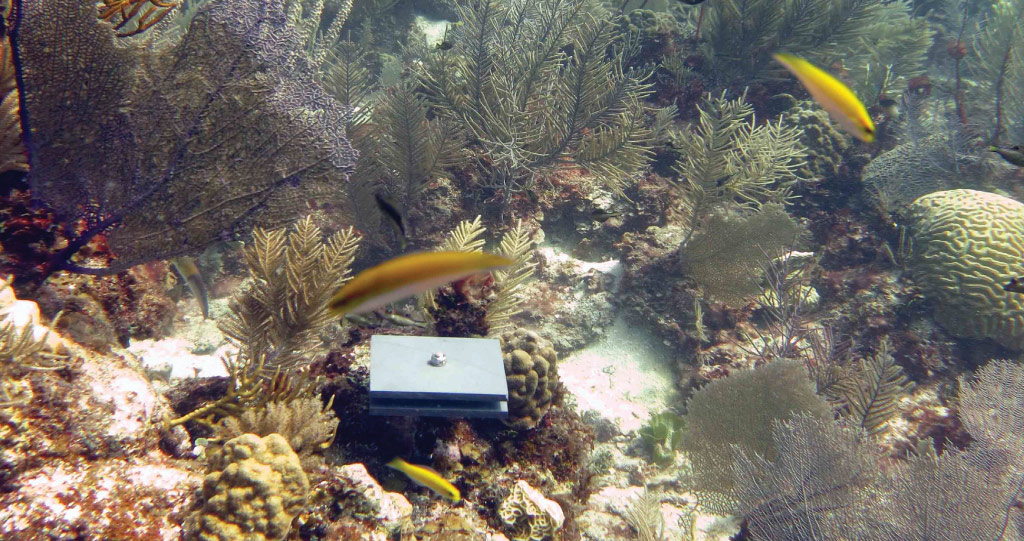

Monitoring and comparing geographically distant coral reefs is now possible using a standardized method for measuring calcium carbonate. © 2022 KAUST; Maggie Johnson. /en/article/1249/checking-coral-reef-health-one-tile-at-a-time

A membrane based on a crystalline metal-organic framework (MOF) material shows very high selectivity for unwanted contaminants in methane gas.

© 2022 KAUST

Monitoring and comparing geographically distant coral reefs is now possible using a standardized method for measuring calcium carbonate. © 2022 KAUST; Maggie Johnson. /en/article/1249/checking-coral-reef-health-one-tile-at-a-time

A blueprint for measuring calcium carbonate on the ocean floor could help marine scientists monitor coral reef health around the globe.

Climate change and pollution from human activities are irreversibly changing many marine habitats, particularly coral reefs. To assess and mitigate future impacts, ecologists must understand how these ecosystems are functioning right now.

One indicator of coral reef health is how much calcium carbonate is produced over time as shells and skeletons of marine animals accumulate on the ocean floor. Researchers often use special tiles on the seabed, which gradually become home to settling pioneering plants and animals. After a year, the researchers retrieve the tiles to see how much calcium carbonate has accumulated on them and which living species are present.

Johnson and her team used special settlement tiles (pictured) that accumulate calcium carbonate over time. Measuring this accumulation indicates the condition and health of the reef.

© 2022 KAUST; Sean Mattson

“To understand how marine ecosystems are changing over space and time we need to be able to compare data collected from different habitats,” says marine scientist Maggie Johnson. “But researchers employ a range of approaches or measure different variables, meaning that the data might not be directly comparable,” she adds. This makes it tricky to create a global picture of marine ecosystem health.

Johnson and her colleagues have developed a standardized method for making and deploying calcification accretion units (CAUs), which are similar to settlement tiles but more specifically are used for measuring calcium carbonate. The comprehensive “how to” guide provides detailed instructions for tile construction and CAU assembly, from material suppliers to measurements, as well as how to place them and retrieve them, all of which will enable researchers to collect comparable data from coral and oyster reefs worldwide.

Using a standard method across the globe’s coral reefs allows scientists to compare coral reef health globally. In the tile pictured above, calcium carbonate has accumulated on the tile over time along with several other marine species.

© 2022 KAUST; Sean Mattson

“Coral reefs cover less than one percent of the seafloor yet provide more than 25 percent of the ocean’s biodiversity,” says Johnson. “Much of this diversity comes from tiny critters living in the unseen cracks and crevices,” she adds. These hidden species, or “cryptic taxa,” cannot be captured by visual surveys, but the CAUs include a small space for these tiny taxa to occupy. “During collection, the tiles must be placed in zipped bags to keep the community of cryptic critters intact all the way to the lab,” says Johnson.

The guide advises immediate processing of the samples, while the animals and plants are still alive. This involves taking high resolution photographs that are later used for spotting species and microscope observations to count baby coral. The calcium carbonate is then removed by a weak acid.

“By weighing the tiles before and after decalcifying them, researchers can calculate how much calcium carbonate was deposited on that tile over a year,” says Johnson. “This figure can help compare reef conditions in different parts of the world or how the health of one reef is changing over time.”

Understanding the impacts of human activities on marine habitats will help researchers and governments find ways to mitigate the negative effects. “This standardized and accessible approach will help promote collaboration and informed decision-making even when using data from all over the world,” concludes Johnson.

References

-

Johnson, M.D., Price, N.N. & Smith J.E. Calcification Accretion Units (CAUS): A standardized approach for quantifying recruitment and calcium carbonate accretion in marine habitats. Methods in Ecology and Evolution Advance online publication, 11 April 2022.| article

You might also like

Marine Science

Measuring spatial differences in reef-building corals to guide future management

Marine Science

Potential gains from replenishing reef fish stocks revealed

Marine Science

A place to trial hope for global reef restoration

Marine Science

Reef-building coral shows signs of enhanced heat tolerance

Marine Science

Plastic-munching bacteria found across the seven seas

Marine Science

AI reveals the universal beauty of coral reef growth

Marine Science

Tiny crabs glow to stay hidden

Marine Science