Bioscience

Rules of inheritance rewritten in worms

Laboratory model breaks laws of heredity, opening up new research possibilities in genetics and synthetic biology.

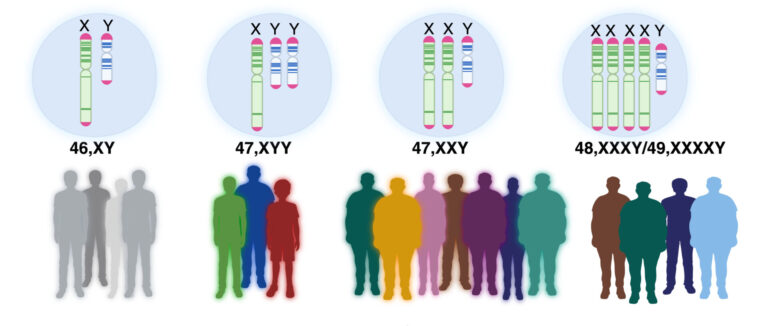

The idea that children inherit half of their DNA from each parent is a central tenet of modern genetics. But a team led by KAUST’s Christian Frøkjær-Jensen has re-engineered this heredity pattern in roundworms, a commonly used model organism in biology, and created animals with an unusual pedigree that are beginning to help scientists better understand nongenetic modes of inheritance and molecular signaling events between tissues and genomes.

“Being able to produce such populations is a game changer for developmental and genetic studies,” says geneticist Frøkjær-Jensen. “We expect these tools to be of substantial interest to the worm research community, as well as to many colleagues working on other model systems for which this approach may provide paradigm and guidance.”

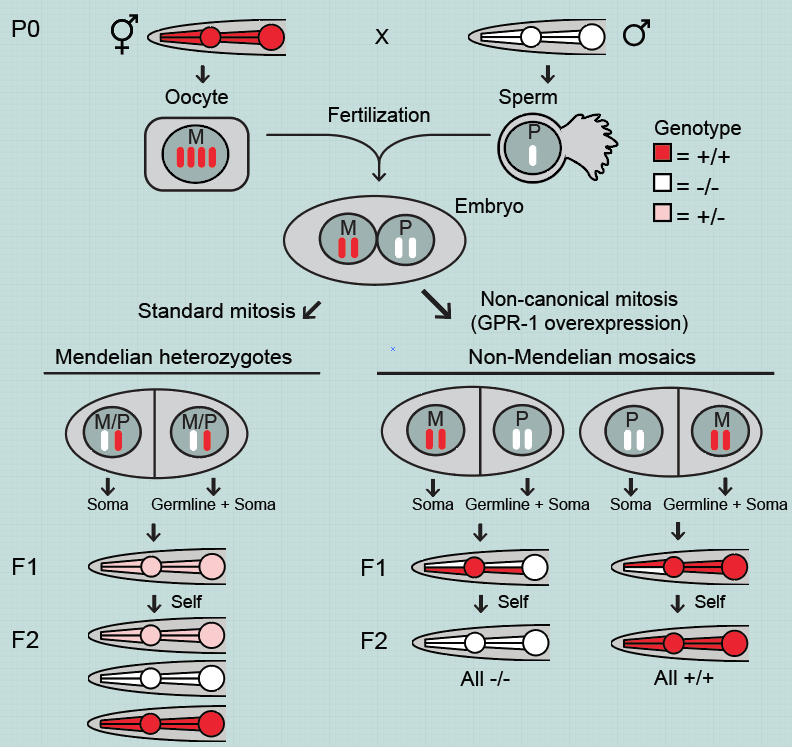

Frøkjær-Jensen and his colleagues describe an easy and reliable way of making these worms. Their method builds on the 2016 work of researchers in Germany, who made a simple tweak to the cytoskeletal structure that forms during cell division. They overexpressed just one gene, GPR-1, which induced faulty sorting of chromosomes in the earliest stage of embryonic development.

This led to mosaic offspring in which certain tissues contained DNA only from mom while other tissues contained DNA only from dad—but the protocol was finicky and unreliable. GPR-1 expression was often lost over time, and the microscopic detailing needed to confirm whether atypical chromosome sorting had occurred was tedious, making it hard to take advantage of the genetic tool.

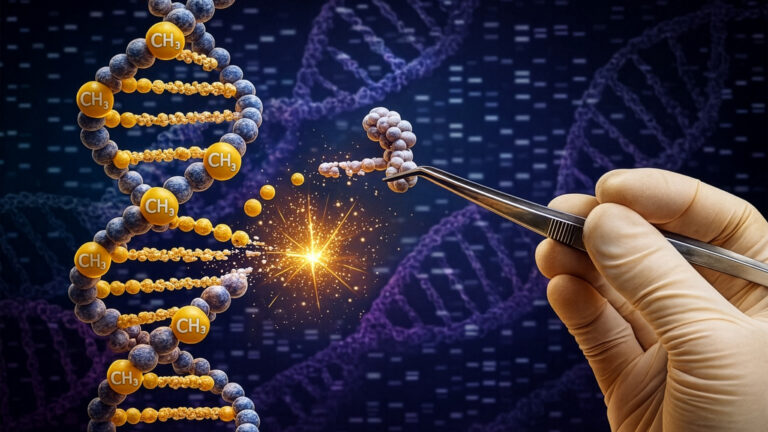

Over-expression of just a single gene (gpr-1) in the early embryo of the roundworm C. elegans allows a fundamental rewriting of Mendelian inheritance. Instead of all cells containing maternal and paternal DNA, the first cell division leads to maternal and paternal DNA being split into two different cells. Germ cells are generated from only one of these cells resulting in grandchildren with DNA exclusively from one of the original parents. Such a system allows us to question fundamental assumptions about inheritance.

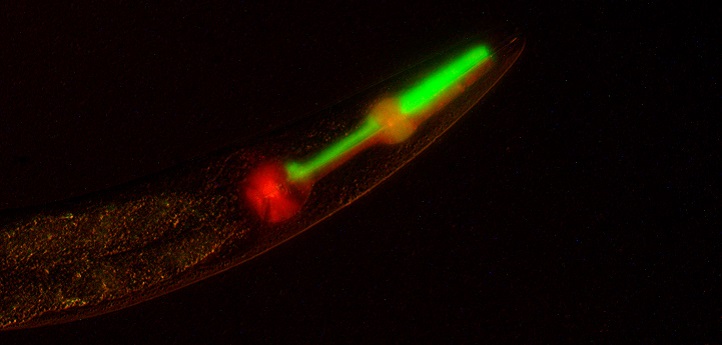

© 2019 Karen Artiles, Andrew Fire and Christian Frøkjaer-Jensen

Frøkjær-Jensen worked with Nobel Prize-winning geneticist Andrew Fire and his lab manager at Stanford University to improve and simplify the German team’s technique. They modified the GPR-1 gene to prevent it from being turned off by genomic defense mechanisms, and they developed a more easily tractable system for visually identifying whether worms were mosaic or not.

The researchers created a library of fluorescently marked, GPR-1–overexpressing strains that offer a platform for interrogating the function of any genes of interest. As a proof of concept, they used these toolkit strains to generate worms containing almost no genetic material from their maternal lineage. Only the DNA found in the mitochondria, the subcellular power plants, came from the maternal lineage, while all nuclear DNA came from the paternal lineage—a departure from the way heredity is supposed to work.

In his KAUST lab, Frøkjær-Jensen is now using the strains to design worms with recoded genomes for applications in synthetic biology. As part of the KAUST Environmental Epigenetics Research Program, his lab is also studying how chemical marks that impact gene expression can be passed from one generation to the next, a phenomenon known as transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.

References

- Artile, K.L., Fire, A.Z. & Frøkjær-Jensen, C. Assessment and maintenance of unigametic germline inheritance for C. elegans. Developmental Cell 48, 1-13 (2019).| article

You might also like

Bioscience

Robust workflow built for chemical genomic screening

Bioscience

Cell atlas offers clues to how childhood leukemia takes hold

Bioscience

Hidden flexibility in plant communication revealed

Bioscience

Harnessing the unintended epigenetic side effects of genome editing

Bioscience

Mica enables simpler, sharper, and deeper single-particle tracking

Bioengineering

Cancer’s hidden sugar code opens diagnostic opportunities

Bioscience

AI speeds up human embryo model research

Bioscience