Chemistry

Saving desalination membranes from minerals and microbes

Treating seawater with selected chemicals before desalination could reduce biofouling and lengthen the lifespan of filtration membranes.

Identifying the components of membrane antiscalants that cause biofouling could help make seawater desalination a more sustainable source of fresh water.

“Safe drinking water is a human right,” says environmental scientist Graciela Gonzalez-Gil, “yet roughly 800 million people have no access.” The United Nations estimates that demand for fresh water could exceed the natural water cycle supply by as much as 40 percent by 2030.

“Seawater desalination — particularly by reverse osmosis (SWRO), which involves pressurizing seawater through a membrane at high pressure to remove salt and impurities — has become a widely adopted low-cost source of drinking water in arid coastal countries,” says Gonzalez-Gil’s colleague and KAUST alumni Ratul Das, who now works as Head of Desalination R&D for energy company ACWA Power, which has 16 water seawater desalination plants across four countries.

However, SWRO is energy intensive, and the used membranes create a lot of waste. Seawater is typically pretreated with antiscalants to prevent the scaling of salt on the membranes. “The low cost of these chemicals compared to other methods helps keep water prices low, hence their popularity,” says Das. But many of them trigger fouling by promoting microbial growth.

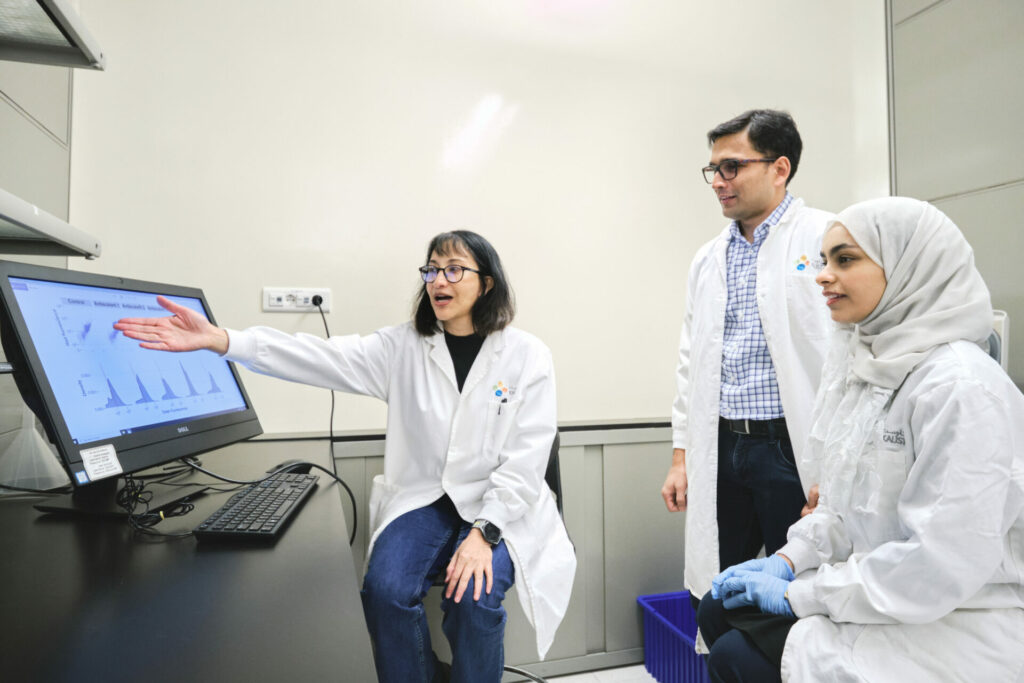

“Desalination operators are not fully informed about why and to what extent antiscalants cause biofouling,” says Gonzalez-Gil. “Measuring the bacterial growth caused by different antiscalants and linking this to their chemical composition can help these operators select products with minimal biofouling.”

Gonzalez-Gil’s team prepared vials of natural seawater with a small starting concentration of indigenous bacteria. Adding one of eight common antiscalants to separate vials, they measured daily bacterial growth and compared this to bacterial growth in seawater without antiscalant.

“We measured the carbon, phosphorous and nitrogen content of each antiscalant and used nuclear magnetic resonance to get a more detailed chemical fingerprint,” says Gonzalez-Gil.

The team found that some antiscalants contained other compounds besides the active ingredients[1]. One particular contaminant – orthophosphate – clearly promoted bacterial growth. “Surprisingly, not all phosphanate-based antiscalants were contaminated with orthophosphates,” says Gonzalez-Gil, “such as HEDP (1-hydroxyethylidene-(1,1-diphosphonic acid), which was also the only antiscalant that didn’t promote bacterial growth.”

The team’s chemical fingerprinting technique could help manufacturers tailor antiscalants to contain fewer bacteria-boosting compounds. “Reducing biofouling will reduce the energy required for SWRO,” says Das. “It will lower the costs of desalination and, by reducing greenhouse emissions, will help to protect the planet.”

Reverse osmosis membranes are currently replaced every three to five years, despite a potential lifespan of 10 to 15 years. “Minimizing biofouling will extend their useful life and reduce the membrane waste deposited to landfill,” adds Gonzales-Gil.

Das hopes to develop a simple low-tech test for use at desalination plants worldwide. “We want to eliminate ‘black boxes’ in the desalination industry and drive greener initiatives that have impact for Saudi Arabia and internationally,” he adds.

Reference

- Hasanin, G., Mosquera, A.M., Emwas, A-H., Altmann, T., Das, R., Buijs, P.J., Vrouwenvelder, J.S. & Gonzalez-Gil, G. The microbial growth potential of antiscalants used in seawater desalination. Water Research 233, 119802 (2023).| Article

You might also like

Chemistry

Turning infrared solar photons into hydrogen fuel

Applied Physics

Natural polymer boosts solar cells

Chemistry

Disruptive smart materials flex with real world potential

Chemistry

Catalysts provide the right pathway to green energy

Chemistry

Hollow molecules offer sustainable hydrocarbon separation

Chemistry

Maximizing methane

Chemistry

Beating the dark current for safer X-ray imaging

Chemical Engineering