Mechanical Engineering

Putting gas under pressure

Understanding the response of gas flames to acoustic perturbations at high pressure should make next-generation turbines safer and more efficient.

Deanna Lacoste (left) and her student Francesco Di Sabatino discuss the advantages of the setup.

© 2018 KAUST

Soldiers marching lockstep across a bridge can cause the structure to collapse if the rhythm of their step matches the bridge’s natural vibration frequency. Combustion engineers must consider a similar effect when designing the gas turbines used in electricity generation and aero-engines.

Just as soldiers’ feet can cause bridge sway to reach the point of destruction, a gas turbine can be damaged, or even explode, if heat and pressure fluctuations produced by the flame couple with the acoustics of the combustion chamber. At a lesser degree, this thermoacoustic instability hampers efficient combustion, increasing noise and pollution emissions.

Predicting and preventing thermoacoustic instabilities remains challenging for the design of a gas turbine. To improve the models used, Deanna Lacoste from KAUST’s Clean Combustion Research Center and her colleagues measured the stability of gas flames at elevated pressure.

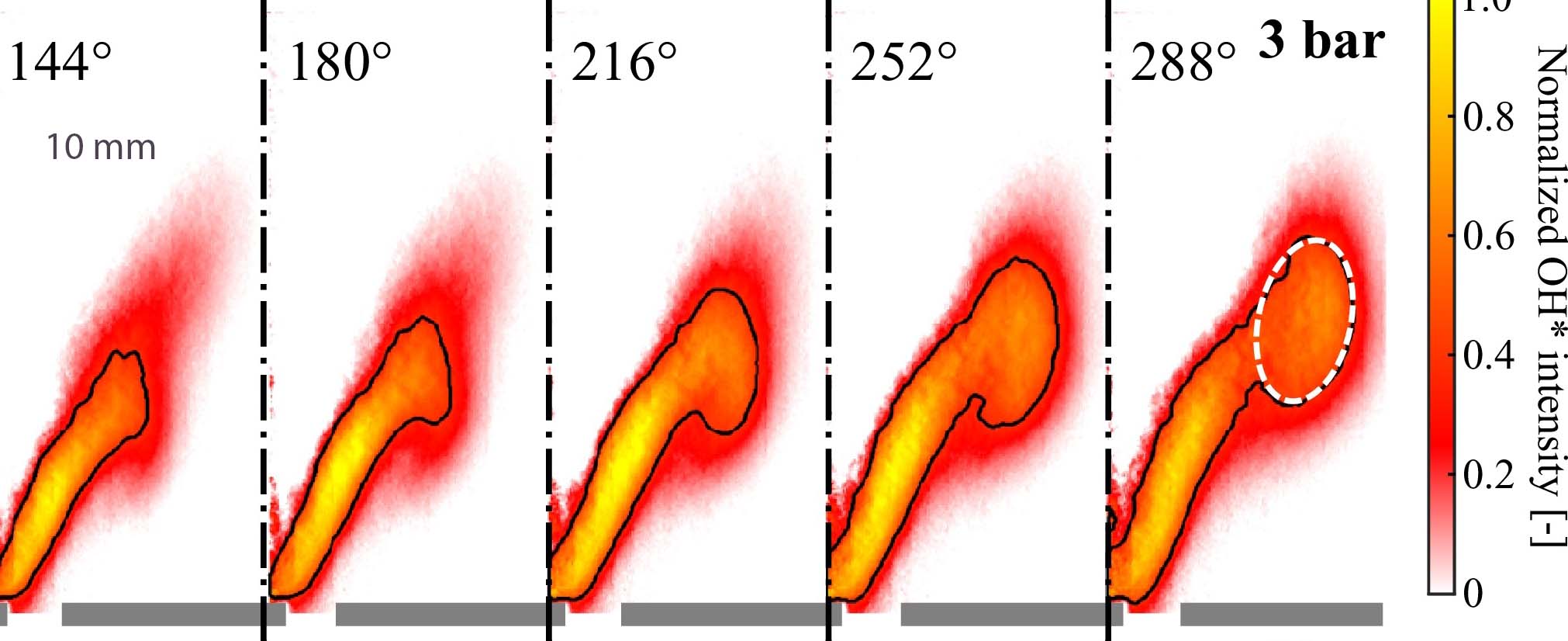

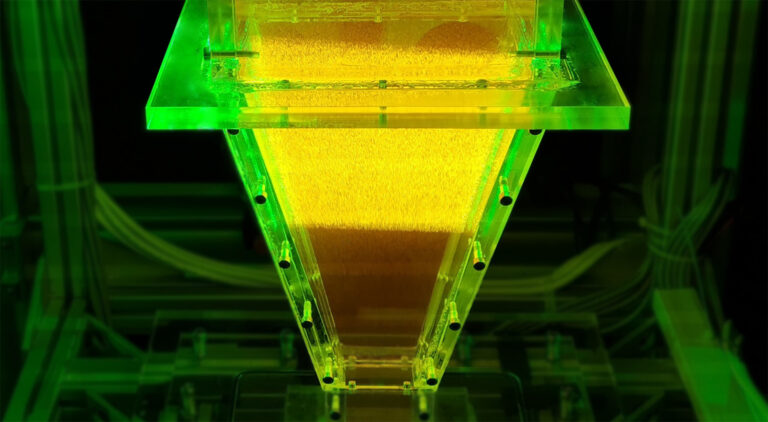

a) A loudspeaker generates the sound waves that test how acoustic perturbation affects the gas flame and b) A cut-away image of the high pressure combustion duct. Windows (far left and right) built into the apparatus enables monitoring of gas combustion.

Reproduced with permission from reference 1. Figure 1a and b © 2018 Elsevier

Investigation of the flame’s response to acoustic forcing uses a parameter called flame transfer function (FTF), says Francesco Di Sabatino, a Ph.D. student in Lacoste’s team. The FTF is derived from experimental measurements of the flame’s response to sound waves. But these experiments are usually run at atmospheric pressure, whereas real gas turbines reach pressures of up to 30 bar.

Lacoste, Di Sabatino and their colleagues systematically investigated the effect of pressure on methane and propane gas flames. “Our experiments show that FTF at atmospheric pressure is different than FTF at elevated pressure,” says Di Sabatino. For both methane and propane gas flames, pressure had a particularly strong effect when the loudspeaker produced acoustic perturbations of 176 Hz.

The new data will assist with the design of new gas turbines, Di Sabatino says. “It will be useful for engineers to have FTFs at pressures closer to the operating pressure of gas turbines,” he says. “One next step of our research is to build a new experimental setup to reach up to 20 bar, closer to the pressures in real gas turbines,” he adds.

References

-

Di Sabatino, F., Guiberti, T.F., Boyette, W.R., Roberts, W.L., Moeck, J.P. & Lacoste, D.A. Effect of pressure on the transfer functions of premixed methane and propane swirl flames. Combustion and Flame 193, 272-282 (2018).| article

You might also like

Mechanical Engineering

Green hydrogen from fluctuating power sources

Mechanical Engineering

Cracking clean fuel combustion

Mechanical Engineering

Tiny sensor could transform head injury detection

Mechanical Engineering

Electrocatalytic CO2 upcycling excels under pressure

Chemical Engineering

Rethinking machine learning for frontier science

Mechanical Engineering

Falling water forms beautiful fluted films

Mechanical Engineering

Innovative strain sensor design enables extreme sensitivity

Mechanical Engineering