Environmental Science and Engineering

Resistance requires a rethink of reused water

Treated wastewater may be suitable for some irrigation uses, but antibiotic-resistant microbes could be cause for concern.

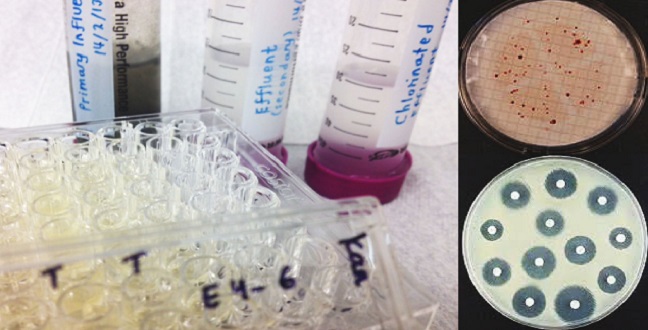

Researchers recovered and isolated bacterial isolates from water samples collected from a local wastewater treatment plant.

© 2015 KAUST

Fresh water is scarce in Saudi Arabia, and the majority of this precious resource is used for irrigation to support domestic agriculture. Some of this water demand could be met by using treated wastewater, and Pei-Ying Hong’s research team at KAUST recently conducted a careful assessment of whether this water is ‘clean’ enough for farm use1.

Hong notes that the total output of Saudi Arabia’s 30 wastewater treatment plants could replace as much as 10 percent of the fresh water now being used for irrigation. Unfortunately, this resource is largely unused because of safety concerns among the general public. “The majority of treated wastewater is reused for industry, landscaping, or for aquifer and river-basin recharge,” she says. “Only a handful of pilot-scale farms in Riyadh utilize treated wastewater to grow agricultural crops.”

Hong and colleagues analyzed the output from one plant in Jeddah over the course of a year, using a variety of techniques to determine the quantity and diversity of the bacterial population in the treated wastewater. On the one hand, the treatment process was generally effective at eliminating known pathogens, including fecal coliform bacteria and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can cause severe infections in individuals with compromised immunity. Based on these widely-used quality criteria, the treated water is suitable for use on non-food crops.

However, the researchers also saw cause for concern. They detected known antibiotic resistance genes in the bacterial genetic material present in the water samples. If released into the environment, these resistance genes could be taken up by other bacteria to confer protection against commonly-used drugs.

In cultivating nearly 300 bacterial samples from the output water, the researchers observed widespread drug resistance. “Although the overall number of bacteria decreased, the proportion of bacterial isolates resistant to six types of antibiotics increased from 3.8 percent in the input to 6.9 percent in the chlorinated output,” says Hong.

Current treated wastewater quality standards do not take this risk into consideration —and Hong believes this needs to change and measures broadened. “There is a need to expand the current regulations beyond simply defining the density of fecal coliforms,” she says. “There may be a need to monitor for the abundance of antibiotic-resistant opportunistic pathogens and to assess microbial risk to mitigate potential risks during reuse.”

Her team now intends to determine the real-world risk from these resistant bacteria, and whether they survive long enough in the environment to pose a threat.

References

- Al-Jassim, N., Ansari, M.I., Harb, M. & Hong, P.-Y. Removal of bacterial contaminants and antibiotic resistance genes by conventional wastewater treatment processes in Saudi Arabia: Is the treated wastewater safe to reuse for agricultural irrigation? Water Research 73, 277–290 (2015).| article

You might also like

Environmental Science and Engineering

Ultrathin water repellent membrane advances desalination

Environmental Science and Engineering

Bacteria reveal hidden powers of electricity transfer

Environmental Science and Engineering

Wastewater surveillance tracks spread of antibiotic resistance

Bioscience

Super fungi survive extreme Mars-like environments

Environmental Science and Engineering

Rethinking food systems to restore degraded lands

Environmental Science and Engineering

Combat climate change by eliminating easy targets

Environmental Science and Engineering

Wastewater treatment to fight the spread of antibiotic resistance

Bioscience