Marine Science

Lockdowns unlock ecology research potential

National lockdowns have provided a unique opportunity to assess the effects of human activity on wildlife, which could translate into new attitudes and better policies.

Restricted movements of people during the COVID-19 crisis allowed the natural world to reclaim habitats. © 2021 KAUST /en/article/1094/lockdowns-unlock-ecology-research-potential

Restricted movements of people during the COVID-19 crisis allowed the natural world to reclaim habitats. © 2021 KAUST /en/article/1094/lockdowns-unlock-ecology-research-potential

When most of the world went into lockdown to limit the spread of COVID-19, ecologists realized that these tragic circumstances presented a unique opportunity to study how the presence, or absence, of humans affects biodiversity.

The freedom to travel and transport goods by land, air or sea has underpinned social and economic progress yet has been costly to the natural world, destroying habitats and contributing to climate change. In April 2020, an estimated 4.4 billion people experienced a full or partial national lockdown, compelled to severely limit their movements. And the natural world expanded its reach.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that wildlife took advantage of the absence of humans.

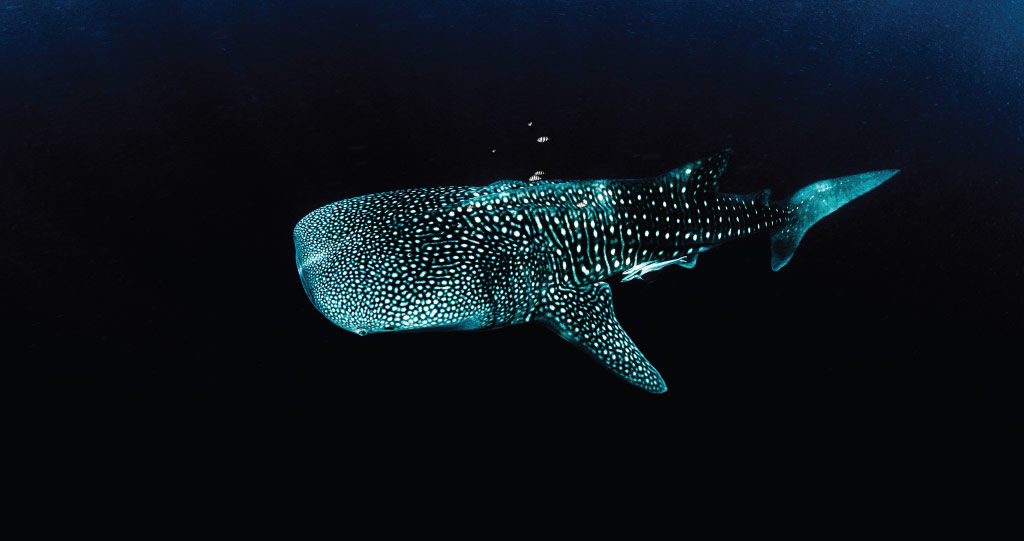

© 2021 Morgan Bennett Smith

As people remained in their homes, wildlife showed up in unexpected places, with many sightings shared on social media. When Carlos Duarte, distinguished professor in KAUST, noticed the rising reports of unusual animal behavior, he launched the PAN-Environment project to connect international researchers studying the ecological impacts of lockdowns.

“Our aim is to use this serendipitous global human confinement experiment to assess the effects of human activity on biodiversity and ecosystems at a global scale,” says Duarte, who leads the project alongside Amanda Bates, a marine ecologist at the Memorial University of Newfoundland, and Richard Primack, an ecologist at Boston University.

Abundant anecdotal evidence during the lockdowns — jackals prowling parks in Tel Aviv, monkeys ruling empty roads in India, a beaver window-shopping in Berlin — suggests that animals took advantage of the absence of humans. But warning signs also showed some species could be at risk as more people descended upon green spaces or began hunting and foraging for their own food. Duarte’s team recognized the need for a quantitative scientific investigation.

Most endeavors to measure humanity’s impact on animals have focused either on changes over space — how biodiversity differs between protected and unprotected areas, for example — or over time — how wildlife in one area responds to short- or long-term changes in human activity. The COVID-19 pandemic created similar perturbations around the world as many countries imposed similar strict protective measures.

The team used traditional wildlife surveys and anecdotal evidence, animal tracking devices, remote sensing, social media and geolocated photographs as sources of data for their survey.

© 2021 Morgan Bennett Smith

PAN-Environment is gathering global data from diverse sources so ecologists can compare animal behavior before, during and after lockdown, as well as between sites with different levels of restrictions, and compare with results from remote or inaccessible “control” sites. This should reveal if reduced human activity really did enable animals to expand their ranges and increase their numbers, and if the lack of conservation efforts left more endangered species exposed.

It is also an opportunity to assess the strengths and weaknesses of existing observation systems and use the findings to improve biodiversity conservation.

Organizing a global research effort amidst lockdown restrictions presents many challenges. “Coordinating large teams around the world is tricky when you cannot meet,” says Duarte, “Fortunately, KAUST sits in a convenient time zone between east and west, enabling me to do so.”

However, with most researchers in confinement, the team could not keep up observations, making it difficult to get robust data sets. “This is where big data approaches can help reduce uncertainties,” he adds.

The PAN-Environment project is gathering global data from diverse sources so ecologists can compare animal behavior before, during and after lockdown.

© 2021 Morgan Bennett Smith

Duarte’s team called upon environmental and citizen scientists, such as the Bio-Logging Initiative, fellow biologists and ecologists, and owners of human mobility data to provide open and rapid access to their observations. By combining diverse data sources, including traditional wildlife surveys and anecdotes, animal tracking devices, remote sensing, social media and geolocated photographs, they hope to gather sufficient real-time data to inform immediate conservation actions.

Anecdotal evidence has already revealed some positives. As industrial activities ceased, air and water quality improved; for instance, daily global carbon dioxide emissions fell by 17 percent at the start of lockdown. Noise pollution also decreased, which may explain animal sightings in harbors and cities. However, the loss of ecotourism in protected areas could cut funding for wildlife protection and antipoaching programs, while canceled biodiversity conferences will delay policies destined to help nations reach the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The lockdown has shown that monumental changes in human behavior are possible, which challenges the notion that the large-scale societal changes needed to combat global crises, such as climate change, are impossible to achieve.

Social and economic progress has been costly to the natural world, destroying habitats and contributing to climate change.

© 2021 Morgan Bennett Smith

Duarte’s team recommends a rapid return to conservation research and education (with pandemic-appropriate safety measures) that prioritize species recovery and habitat protection. “Humanity’s role as custodians of nature is impacted when our ability to remain active is impaired,” says Duarte. He is optimistic that their work will benefit both humans and animals. “As we move on from COVID-19, lessons from PAN-Environment will help us balance our role in the biosphere,” he says. “Limiting activities that negatively impact wildlife, while promoting those that benefit the natural world, will ultimately feed back into healthier lives.”

For now, there are vast volumes of data to process, publish and act upon. “What we learn from this experiment could transform the way humans relate to the species we share the planet with,” says Duarte. From this unforgettable crisis, people may rediscover the benefits of a healthy environment, and, as the team concludes, “replace a sense of owning with a sense of belonging.”

References

- Bates, A.E., Primack, R.B., Moraga, P. & Duarte, C.M., COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown as a “Global Human Confinement Experiment” to investigate biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation 248, 108665 (2020).| article

- Rutz, C., Loretto, M-C., Bates, A.E., Davidson, S.C., Duarte, C M., Jetz, W., Johnson, M., Kato, A., Kays, R., Mueller, T., Primack, R.B., Ropert-Coudert, Y. & Tucker, M.A., Wikelski, M. & Cagnacci, F. Comment: COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nature Ecology and Evolution 4, 1156-1159 (2020).| article

You might also like

Marine Science

Potential gains from replenishing reef fish stocks revealed

Marine Science

A place to trial hope for global reef restoration

Marine Science

Reef-building coral shows signs of enhanced heat tolerance

Marine Science

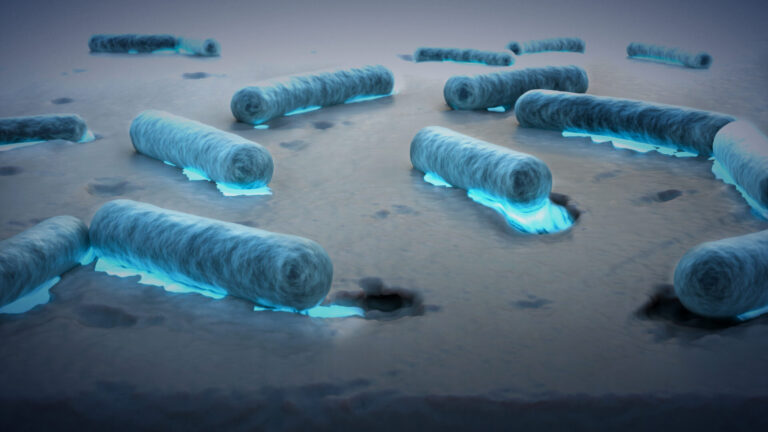

Plastic-munching bacteria found across the seven seas

Marine Science

AI reveals the universal beauty of coral reef growth

Marine Science

Tiny crabs glow to stay hidden

Marine Science

Mass fish deaths linked to extreme marine heatwave in Red Sea

Marine Science