Marine Science

Seeking adaptation for corals in times of stress

The Red Sea provides opportunities to coral bleaching and inform future practices to help safeguard the world’s coral reef ecosystems.

Research at KAUST is providing insights into questions about coral bleaching, how it affects reef ecosystems and how it could be minimized.

© 2017 Anna Roik

The Red Sea, with high levels of salinity and exposure to some of the highest sea temperatures on Earth, provides an ideal base for exploring the potential impacts of global warming on fragile marine ecosystems. With a recent rise in the incidence of coral bleaching occurring on reefs around the world, KAUST researchers are providing an important contribution to understanding the phenomenon and how to help corals survive in the future.

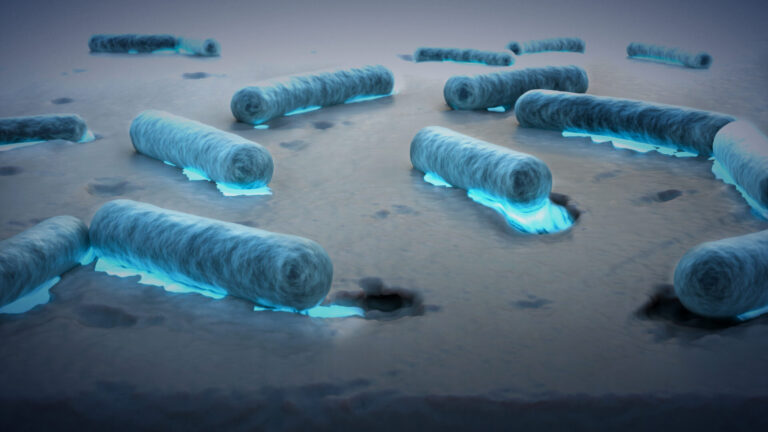

“Coral bleaching is a complex phenomenon that occurs when corals get stressed,” said Michael Berumen, who works in marine biology alongside Carlos Duarte, Christian Voolstra and their teams at the Red Sea Research Center.

“Coral has a somewhat surprising stress response, which is to “kick out” certain types of algae that live symbiotically within the coral tissue—although we don’t know exactly why it does this,” Berumen explains. “The algae give corals their colors, so you can see right through to the white skeleton of the coral animal when bleaching occurs, hence the term.”

Coral bleaching has the potential to reverse: algae may be able to return to the corals and help revive and replenish the reef. However, if certain stressors, such as high temperatures and fluctuating nitrogen levels, continue for an extended period, the corals cannot recover and eventually die.

Recently, scientists have become increasingly concerned for the future of these fragile yet vital ecosystems following wide-scale bleaching events of increased severity right across the globe.

“In a recent assessment, we estimated that 25-30 percent of all reefs in the Red Sea were bleached in late 2015,” said Voolstra. “My team study corals as metaorganisms—the coral animal, the algae symbionts and the bacteria that reside together interact and help each other in specific ways. The relationship is carefully balanced and offers significant benefits for the organisms involved.”

Voolstra’s team is conducting a genome sequencing study on corals from the northern and southern Red Sea hoping to identify gene variants that make the corals respond differently from one part of an ocean to another.

“The Arabian Seas represent the warmest (and coldest) ocean basins where corals live successfully,” said Voolstra. “We aim to pinpoint the specific adaptations of these corals that make them so resilient. We recently showed that some corals associate with a particular algal symbiont, Symbiodinium thermophilum, which is very tolerant to heat and salinity change, thus increasing their resilience. This could one day prove to be a useful tool in helping corals survive extreme conditions.”

However, these potential solutions should be approached with caution, say the KAUST team. While certain symbionts can increase resilience, it is just as important to consider all the other stressors that contribute to bleaching and what can be done to limit them.

“Maintaining a healthy overall balance on every reef is crucial,” said Duarte. “While we may not be able to prevent bleaching completely, we can help reef recovery by limiting marine pollution and upholding strict fishing laws in specific areas, for example.”

One of the best examples of monitoring coral bleaching stems from Australia, where parts of the Great Barrier Reef were closely watched and analyzed by a collaboration between 14 institutions in early 2016. While this level of analysis is not yet possible in the Red Sea, KAUST is well-placed and well-resourced to enable researchers to conduct careful, methodical investigations on a local level that will provide insights for other sites around the world.

To this end, Berumen and his team are conducting surveys of individual reefs in the southern Red Sea, where significant and widespread bleaching occurred in late 2015, resulting in coral mortality rates as high as 50-90 percent in some localities. Combining their observations of marine life with satellite data regarding changes in water temperatures around reefs can give insights into how temperature fluctuations affect corals and how temperature thresholds for bleaching can change from place to place.

“Reconstructing the past ecology of the Red Sea from sedimentary data taken from seabed cores is also invaluable,” said Duarte. “This is another aspect of our work that may help inform future marine management.”

“The situation with corals around the world gives us an opportunity to work together and limit further damage,” added Voolstra. “We cannot afford to lose corals because this means we will lose other ecosystems too.”

References

You might also like

Marine Science

Potential gains from replenishing reef fish stocks revealed

Marine Science

A place to trial hope for global reef restoration

Marine Science

Reef-building coral shows signs of enhanced heat tolerance

Marine Science

Plastic-munching bacteria found across the seven seas

Marine Science

AI reveals the universal beauty of coral reef growth

Marine Science

Tiny crabs glow to stay hidden

Marine Science

Mass fish deaths linked to extreme marine heatwave in Red Sea

Marine Science